Lifestyle change

The adherence problem

Author: Frederik Kehlet

20–30 minute read

Lifestyle plays a key role in the development and treatment of many conditions. Whether we're talking about nonspecific pain, cancers, cardiovascular diseases, or any other chronic (or even acute) illness, a sizable chunk of the condition's etiology and severity is often directly attributable to modifiable lifestyle factors. Both from a scientific as well as a common-sense perspective, the way a person lives their life is an important factor in determining their health outcomes.

However, many clinicans feel that getting their patients to change their lifestyle is a monumental task. Forget about trying to avoid consequences far off in the future, even if the individual is experiencing symptoms right now, they just won't listen! They've got plenty of reasons to do something about their problem and we're telling them exactly how to fix it...

Why don't they do what we say?

Let's unpack the answer to that question.

What is lifestyle?

We'll need an operational definition of lifestyle in order to make sense of it:

"The summation of a person's consistent behavioral patterns deeply connected with their identity."

Identity can be loosely understood as the characteristics which define an individual and their sense of self (interests, opinions, beliefs, values, etc.).

When we talk about lifestyle change, what we're referring to is behavior change + identity change. You cannot sustain one without the other. Any theory that claims to tackle behavior change must also deal with identity. We'll examine a theory that addresses both as we start to untangle the following question:

What drives behavior?

The key word here, "drives," isn't the most apt term for our purposes. We're specifically interested in its synonym motivation, more widely used in professional settings. Understanding motivation, the why of behavior, is the key to understanding how to change behavior.

Motivation

How many times have you heard, "he has low motivation," "she needs more motivation," or even, "we need to motivate our patients more?"

Motivation is a concept often described as a linear quantity. You just need more of it if you want to be successful in adhering to a behavior, and it's our job as clinicians to "give" high amounts of motivation to our patients.

This interpretation of motivation is tightly coupled with the binary reward (the carrot) and punishment (the stick). In order to increase motivation, we increase the degree of punishment or reward. It's elegant in its simplicity. But this simplicity is an illusion.

Many people still hold the belief that motivation works like this; however, we'll come to see that it's an untenable position to hold. This reductionist approach often backfires and results in poor outcomes and patient and clinician dissatisfaction. We have to reframe our idea of what motivation is and where it comes from if we want to be successful in helping patients make positive lifestyle changes.

Theories of motivation

The past century there have been various competing theories that have emerged from the field of motivational psychology. Some of these theories build directly on previous work, while others provide complementary perspectives. Each of the theories attempts to analyze motivation from a different angle. Humans are complex animals, and the reasons which ground our behaviors even more so.

We can split these theories of motivation into two broad categories: content theories, concerning what makes up motivational states, and process theories, how those motivational states arise.

Examples of content theories

- Alderfer's ERG theory

- Herzberg's motivation-hygiene theory

- Maslow's hierarchy of needs

- McClelland's three needs theory

Examples of process theories

- Adams' equity theory

- Bandura's self-efficacy theory

- Skinner's reinforcement theory

- Vroom's expectancy theory

Self-determination theory (SDT)

In this article we're going to focus on a macrotheory (a theory which encompasses several minitheories) of motivation, self-determination theory. Since psychologists Richard Ryan and Edward Deci formulated the first version of SDT in the 1980s, it has been the subject of intense development and research.

Today, SDT stands as one of the most, if not the most influential theory of motivation. It has a massive body of literature supporting its use across a broad spectrum of contexts, from coaching athletes to teaching in schools, trauma counseling, leadership in the military, and beyond. If you're interested in the literature, check out the official website, where all of the research on the theory to date is compiled and organized by topic.

Humanistic origins

SDT traces its roots back to humanistic psychology, a branch of psychology which concerns itself with the individual's journey toward greater autonomy and self-actualization. Humanistic psychology is deeply woven into the fabric of SDT, starting with the theory's principal axiom:

"...people are active organisms, with evolved tendencies toward growing, mastering ambient challenges, and integrating new experiences into a coherent sense of self. These natural developmental tendencies do not, however, operate automatically, but instead require ongoing social nutriments and supports." (selfdeterminationtheory.org)

According to SDT, we naturally take an interest in overcoming obstacles and integrating these experiences into our identity. We all tend toward personal growth, but whether or not this happens critically depends on our environment.

Basic psychological needs

The question then becomes, what are the specific criteria in the environment which either support or thwart personal growth (and as a consequence, self-realization)? SDT defines three basic psychological needs which must be satisfied: autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

"To the extent that the needs are ongoingly satisfied, people will develop and function effectively and experience wellness, but to the extent that they are thwarted, people will more likely evidence ill-being and non-optimal functioning." (selfdeterminationtheory.org)

Autonomy

First up is autonomy, the desire to be the causal agents of our own actions. Irrespective of whether or not free will exists, SDT postulates that the subjective feeling of being in charge of your own choices and the feeling of psychological freedom this brings with it is necessary to be a healthy, functioning organism. Being self-motivated (also called autonomous regulation) leads to healthier outcomes compared to when we are told what to do (controlled regulation). We'll come back to and expand on the idea of "regulation" shortly.

Competence

When we choose to engage with a behavior, we seek a sense of control over the results of the behavior; we all want to experience mastery. Self-efficacy is a well-known determinant of long-term patient outcomes, and supporting a person's feeling of competence increases and sustains their confidence in their own abilities.

Relatedness

Humans are social animals, and we have a deeply rooted desire for belonging and connection with other people. Relatedness includes your sense of place in the world, the feeling that others care about you, and the knowledge that you benefit those around you.

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

SDT pioneered the idea that motivation can be described not only in terms of its quantity, but also its quality. Intrinsic motivation is the natural drive to seek out challenges. It derives from the enjoyment of and interest taken in the behavior itself. Intrinsic motivation is positively correlated with cognitive and social development, task performance, and well-being.

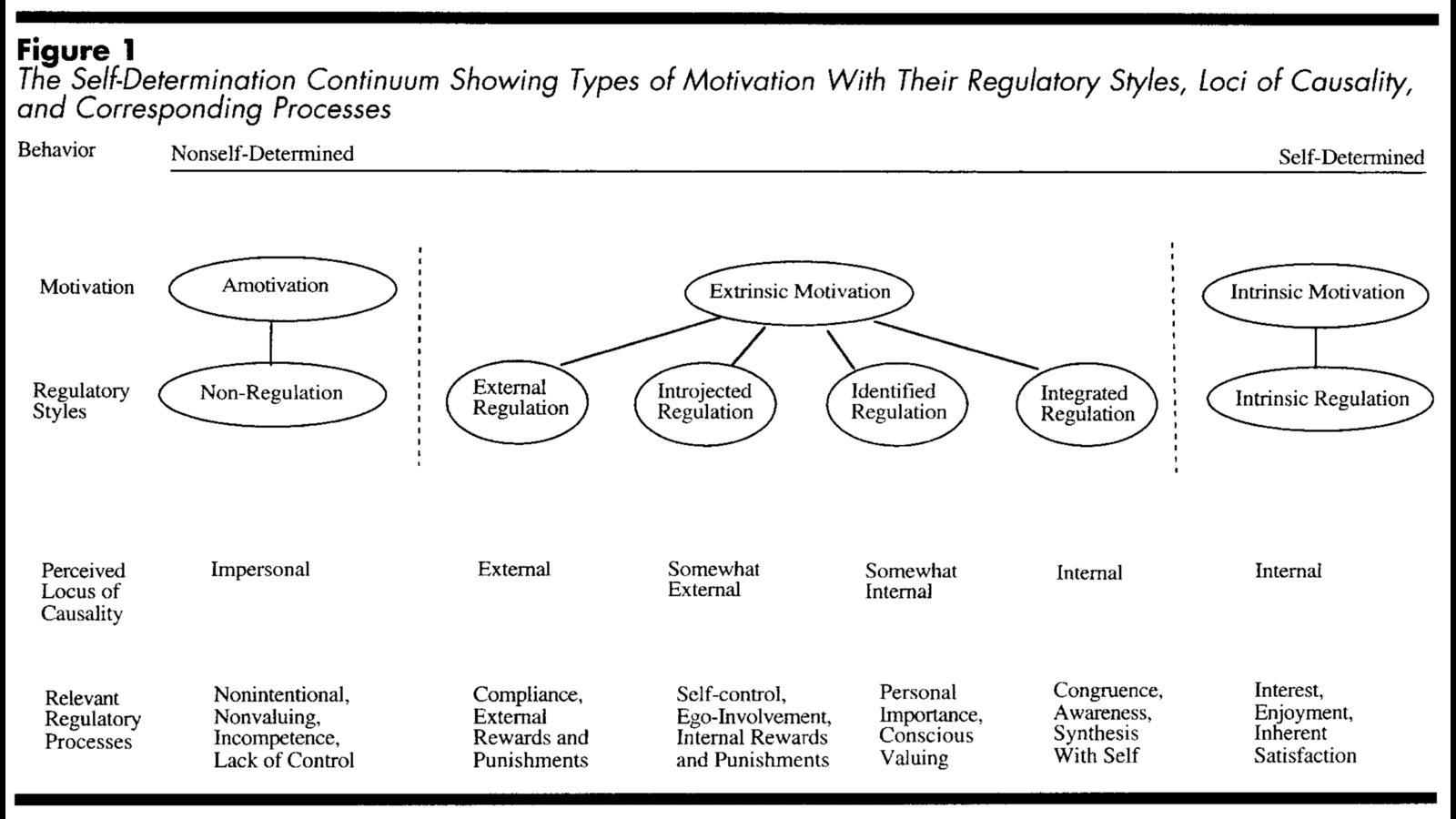

When the goal of a behavior is something other than the behavior itself, we're talking about extrinsic motivation. SDT expands on the concept of extrinsic motivation by delineating distinct subtypes, each defined by the degree of internalization of the behavior's regulation.

"Internalization of regulation" sounds complicated, but it's actually a relatively simple concept: does the thing which is making you act out the behavior (the regulation) come from outside yourself, from within, or somewhere in between (the degree of internalization)?

Types of extrinsic motivation

External regulation is the least autonomous, most "controlled" kind of motivation. Behaving in accordance with known or predicted external punishment or reward is a hallmark of externally regulated behavior. Motivations characterized by external regulation have a clearly defined, externally perceived locus of causality. The individual's sense of volition and control over their actions is absent.

Introjected regulation is characterized by internal rewards and punishments. Introjection is the voice in your head echoing external pressures, the internalization of others' thoughts and attitudes. Pride, social status, and other ego-related motivations are examples of introjected regulation. It is still characterized by an external locus of causality as this kind of regulation is not fully integrated with the self.

Identified regulation is the stage where self-determination gains a foothold. The individual starts to value the behavior because it contributes to a personally relevant goal; the locus of causality turns inward.

Integrated regulation is the most autonomous kind of extrinsic motivation. The behavior is not only deemed valuable in terms of other outcomes, it is also integrated with other aspects of the self. While integrated regulation is still "extrinsic" because the desired outcome is not the behavior itself, it can exhibit similar qualities and benefits to intrinsic motivation.

A spectrum of self-determination

Combining these concepts, we start to paint a picture of a continuum of motivation. One end represents extrinsic motivation in its most controlled form (external regulation), gradually becoming more and more self-determined until we arrive at integrated regulation and intrinsic motivation.

Source: Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000)

There's one more "type" of motivation we have not yet talked about, shown in the diagram above: amotivation. It lies beyond external regulation; a person who is amotivated is totally indifferent and sees no point in pursuing the behavior in the first place. The behavior in question is entirely without regulation and the locus of causality is impersonal, neither external nor internal.

Amotivation aside (we'll return to it later), the motivations grounding our healthy behaviors will, over time, shift from being characterized by external "controlled" regulation to internal "autonomous" regulation given that our environment supports our basic psychological needs.

A number of positive side effects emerge as a result. Our task performance and activity engagement improves, we are more persistent in the face of obstacles and setbacks, and we become more confident and better functioning.

The marathon runner

A natural consequence of SDT is that there is rarely only one kind of motivation behind a behavior. We'll illustrate this with a thought experiment. Imagine that you just finished a marathon. What motivated you to train for and participate in the race?

At the end of the race, there are likely free food and drinks. Perhaps you'll be given a medal contingent on your performance. If those were the only reasons you had to train and run in the marathon, you probably wouldn't have followed through with it (external regulation).

The medal you were chasing could also represent an internal pressure to beat your personal record. Maybe your parents pressured you to perform well in sports when you were a kid. Those thoughts could well have stayed with you as an introjection. Or you saw the race as a way to elevate your status in your social circle by beating your friends' race times (introjected regulation).

The desire to run this marathon and get a medal could also be tied to your personal goal of running a sub-3 hour marathon. This was a stepping stone to achieving that (identified regulation).

You see yourself as an "fit person" and a "competitive athlete." Running marathons and beating the competition constitutes a part of this identity (integrated regulation).

Finally, you run and race for the sake of it. It just feels good to run long distances as fast as you can (intrinsic motivation).

Ask those around you at the finish line and each participant will point to different reasons to justify their decision to participate. Some people's decision to participate may have been dominated by external and introjected regulation, while others are so intrinsically motivated by running that they signed up just for fun.

Analyzing behaviors in terms of their constituent motivations and identifying the types of regulation which dominate the "motivation profile" can give an idea of where to focus your efforts if you want to encourage persistence, engagement, and well-being.

Implications for clinical practice

Let's take a step back and revisit the question we asked ourselves at the beginning of the article:

Why don't they do what we say?

We're now in a position to see this question in a new light. The question itself is holding us back.

Controlling others and threatening them with the future consequences of their behavior results in the worst kind of motivation one can have. A clinical approach to lifestyle change informed by motivational psychology demands that we do not attempt to motivate our patients in this way. We should instead create an environment which is supportive of our patients' basic psychological needs, and the rest will follow.

Manipulate the clinical context

We can think of the environment surrounding the clinician-patient interaction as the clinical context. From the clinic's physical setup to our body language, everything we do and say has the potential to positively or negatively influence our patients' sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

We can make a powerful impact on shaping healthy behavioral patterns and well-being through the context we create. Think about how you can support the basic psychological needs of yourself and those around you, irrespective of whether you're inside or outside of the clinic.

Be a lifestyle coach

The lessons we have learned from SDT encourage us to rethink the entire foundation of our clinical practice. It demands a total change in mindset: to stop taking on a parental role when working with patients. You are now their lifestyle coach. You want to help your patients achieve their goals, but you do not get to decide their goals for them. Don't enforce a hierarchy.

Naturally, situations arise where it's not this obvious and clear-cut. If a patient surrendered all decision-making to you of their own volition, what should you do? You could respect their will and create their entire treatment plan for them, but would this be the best way of supporting their autonomy and competence?

Perhaps an even better solution would involve continuous education and encouraging the patient to experiment and take control of their own health. Not every patient will respond well to this right away (especially if they have been conditioned to be passive in their enviroment—see causality orientations theory, a minitheory within SDT), but it's a good long-term target.

Amotivated or conflicted?

If a patient is truly amotivated when it comes to changing a specific lifestyle behavior, there is not much you can do. A person must be at least somewhat willing to change if they are to have any hope at all in succeeding. However, even though it might seem like many patients are amotivated, when you dig beneath the surface most people are not actually indifferent when it comes to making positive changes for their health.

Patients who presents as amotivated might just possess conflicting motivations. These could stem from negative past experiences and/or a suppressive environment. Maybe the person is unsure of their own values and life goals.

A complex internal motivational struggle can masquerade as indifference and amotivation. It's your job as a lifestyle coach to pull the "puzzle pieces" of your patients' motivations out of them, lay these pieces on the table, and then help your patients put together the jigsaw puzzle of their life.

It cannot be overstated how essential trust and empathy are during this process. Without a strong therapeutic alliance, there is very little chance your patients will open up and be honest with you about themselves. It takes good communication and sharp critical reasoning skills to navigate a person's internal landscape.

Motivational interviewing (MI)

Motivational interviewing is a therapeutic technique which was developed specifically for counseling behavior change. MI has its roots in addiction counseling, but it has since been applied successfully in many other contexts, similar to SDT. Some people working on MI have even looked to SDT to explain why it works.

Although we won't fully explore how to do MI in this article, we've already laid a solid foundation for practicing the technique. Asking open-ended questions and reflecting questions back to the patient to help them reach conclusions by themselves (autonomy support), focusing on past successes to build self-efficacy (competence support), and listening in an active and empathetic way (relatedness support)—these are all cornerstones of MI.

The decision matrix

Making a decision matrix (also called a decisional balance) is an activity sometimes done in MI which can help an individual strengthen their commitment to a behavior change. First, draw a 2x2 table. The patient then identifies the benefits and drawbacks of either continuing with the status quo or making a change.

See an example decision matrix (PDF), also available on motivationalinterviewing.org.

As you work through this activity and the patient writes down their pros and cons for each option, they will get a clearer picture of what making a change would entail.

During this process you are a guide—support the patient's basic psychological needs and do not tell them what to do or what to think. Instead, ask questions. By having patients connect the dots themselves, you can get them moving on the path toward autonomous regulation of healthy behavior.

Summary

In this article, we explored a common clinical frustration:

"Why don't patients do what we say?"

To answer this question, we first gave a concrete definition to lifestyle, recognizing that the identities connected with lifestyle behaviors are just as important as the behaviors themselves.

Self-determination theory showed us that the reasons underpinning our behavior can be extremely complex. It gave us a framework to identify and categorize different kinds of motivation, as well as some guiding principles of how to move people toward healthier motivational states.

We discovered that the question we posed at the beginning was actually loaded with unhelpful assumptions. Instead of telling people what to do, we should focus on creating an environment which is supportive of individuals' basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

We briefly introduced motivational interviewing, a counseling technique designed to facilitate behavior change. Finally, we learned how to use a decision matrix to help patients strengthen their commitment.

Further reading

https://selfdeterminationtheory.org (official website)

Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health

Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review